What would you do if you could do anything? Not superhero anything, but if you woke up tomorrow and had all your bills paid from now until forever, what would you do with your time? Take your dream job that pays far less than your current one? Write your magnum opus? Volunteer full-time? Whatever you answer, the premise is the same. Financial independence means being master of your own time.

Some people call this retirement, some call it independent wealth, and some getting out of the rat race--but in every case the goal is the same: to reach a point in life when you don’t need to work for a paycheck anymore. There are countless books that claim to have the “secret” to unlocking this path, but really there is no secret. By learning a couple of simple economic concepts, the way forward becomes obvious. You’ll still need to do the hard work, but at least mapping your course will be easier.

Personal Economics 101

Here, I’m going to lay out for you a simple way of thinking about economics and personal finance that can help you make strong moves toward financial independence.

Economics is the study of how we direct our limited resources to meet all our needs. All the complexity boils down to that. Now, each of us is basically running our own little economy. We have resources, and we have needs. How we direct those resources affects how many of our needs will get met, how well, and for how long.

Here’s the big idea: In economics, we learn that there are only three ways to produce income--land, labor and capital. If you want to stop laboring (retire, reach financial independence, whatever), then you need to acquire other two.

Land creates income in all kinds of ways. You can rent it to others, sell the trees or other resources on the land, farm it, or just let its value appreciate over time. Labor, we all know about. Capital is all the other “stuff” that can be used, rented, or put to work. We typically think of three types of capital. Physical capital is stuff. For example, if you own a tractor, you can use it to produce value on your land, or you can rent it out to someone else. In both cases, the physical capital is creating value for you. Intellectual capital is the value of any assets you have based on legally protected ideas, like patents or books. Financial capital is just money itself.

The Path to Freedom

From these three sources come all the various income streams we can imagine. Some people are fortunate enough to start life with enough land and/or capital that they never need to labor for income. Most of us are not. Most of us, in fact, start without land or capital, and all we have to work with is our ability to labor. So, how do you get from using labor as your single source of income to the goal of not laboring anymore? You have to make a plan for how you will direct the flow of income from that labor toward investments in land and/or capital.

Needs: Past, Present and Future

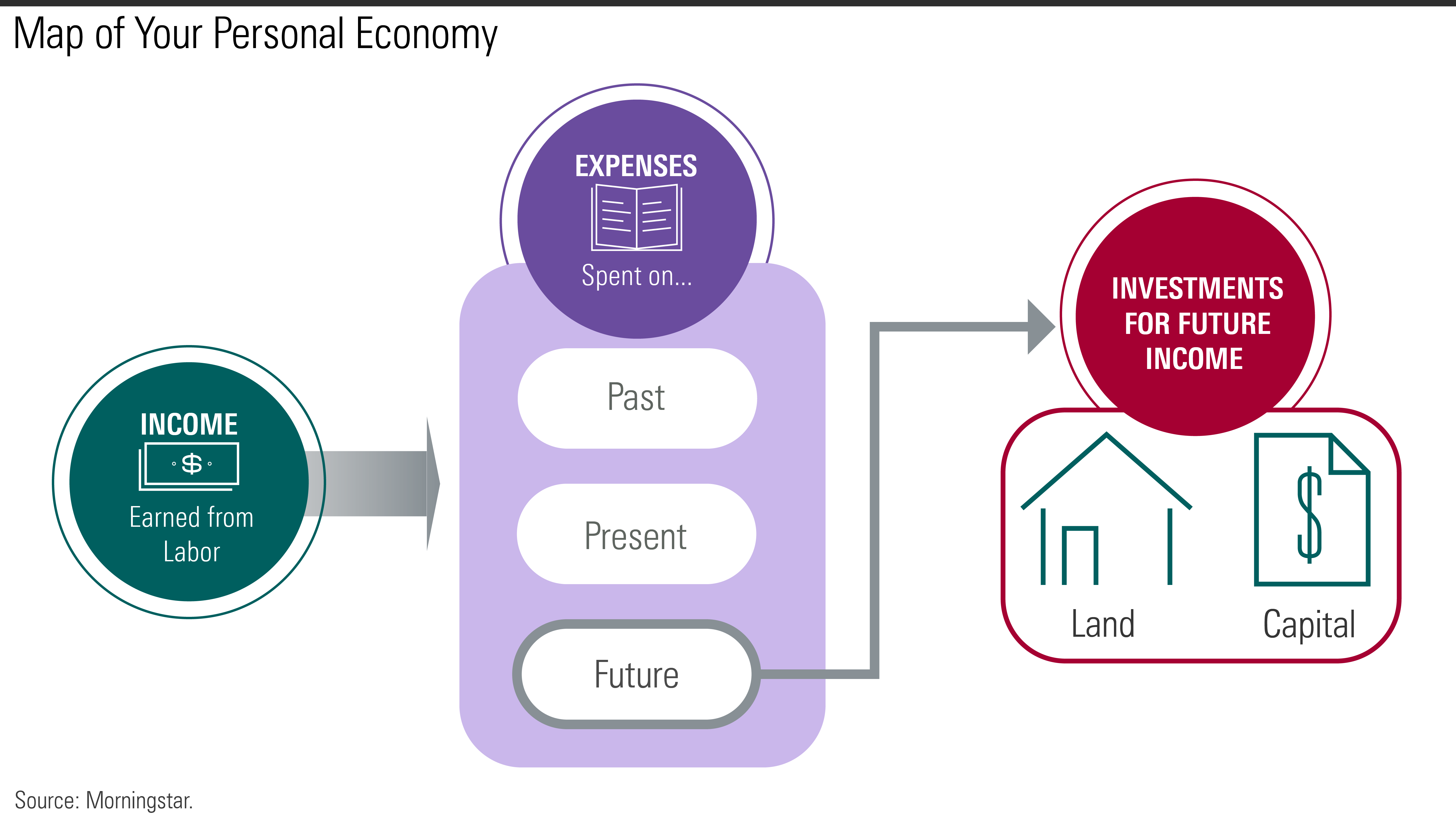

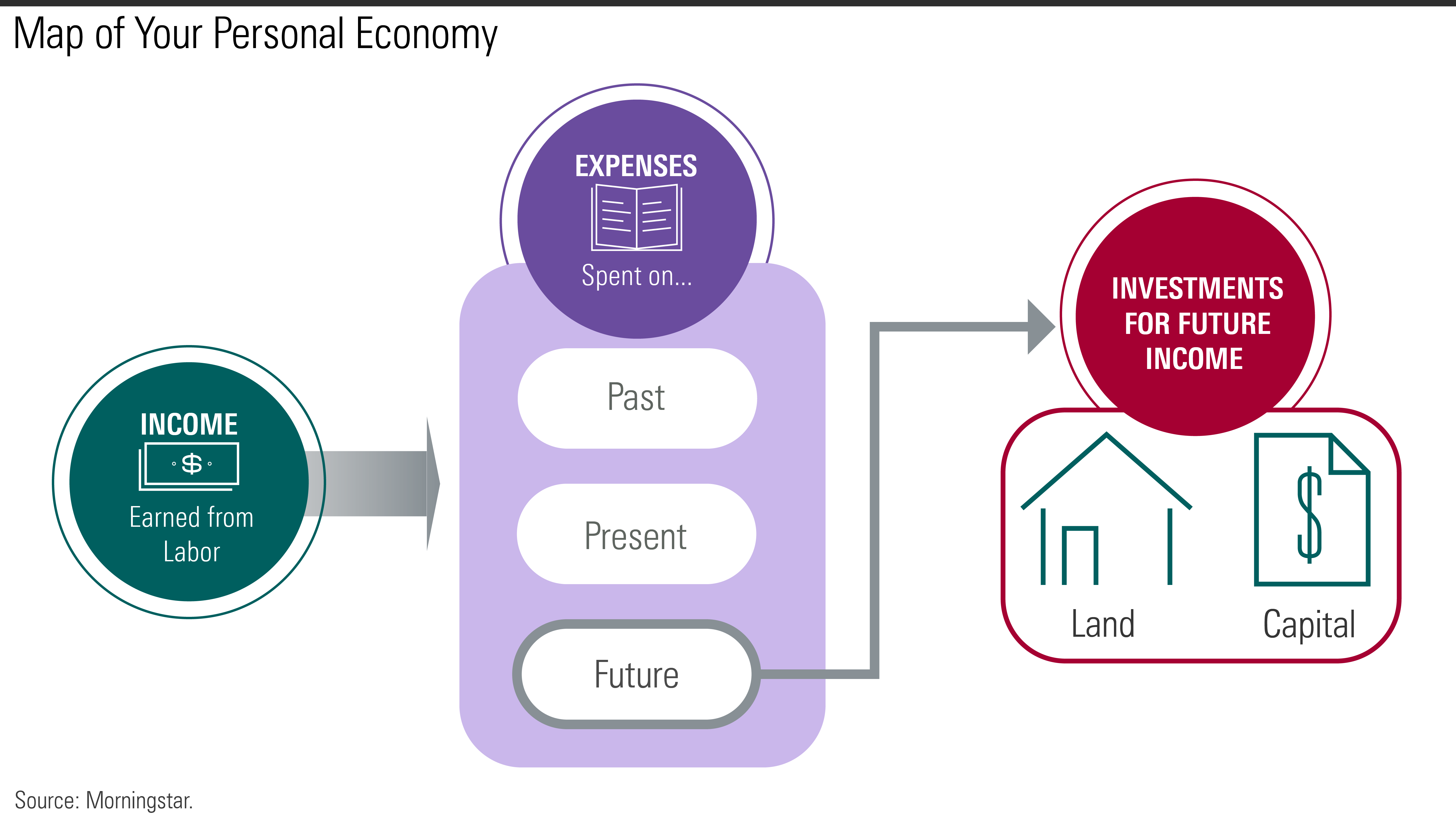

Remember that economics is all about using our resources to meet our needs, and needs are a big part of the picture here. Now, we could talk about Maslow’s Hierarchy, or break our spending down into categories of “needs” and “wants,” but I’m going to suggest we do away with all of that and make it even simpler. Your needs fall into three categories: past, present, and future. With this idea, we can make a map of your personal economy that looks like this:

Your current labor income is divided up into payments toward money borrowed in the past, meeting the needs and wants of the present, and investing in income for your future.

Directing your “future” funds into land or capital slowly over time builds up income sources to eventually replace your income from labor.

Why It Matters

Simple rules of thumb help us by directing our focus to the most important thing(s) and ignoring everything else. This model of personal economics allows you to ignore all the details that make budgeting a huge pain in the neck, and it simplifies the problem into two steps. The first step: Making sure that you are directing some portion of your labor income toward land and/or capital. Otherwise, financial independence is simply not possible. To do this, you may need to take a hard look at how much of your income is going toward past purchases (which could motivate you to avoid adding to your debt in the future), or you might want to rethink the speed at which you spend on your current lifestyle.

This framework puts decisions about day-to-day purchases and borrowing into a long-term perspective. If you can’t find ways to invest for the future, you’re stuck with labor as your only source of income. If the future feels too far away to be real, try using the techniques I laid out in my previous article on Present Bias.

This way of mapping things also helps put investment in perspective. The point of investing is to store up land and capital that will provide you with sustainable income. Focusing on that can help you weigh your choices. How secure is the income stream going to be? When comparing one investment over another, you can estimate them in terms of future income rather than initial value.

For Example

My mother recently retired from her job as a social worker and mental health counselor. She achieved this freedom despite spending many years as a single mother of four children with a low salary. How did she do it?

1) PAST -- She limited borrowing. When she invested in a master’s degree (more skilled labor meant a higher salary after graduation), she took one evening class at a time while working during the day, taking advantage of her employer tuition reimbursement to avoid debt. It took her many years, but she emerged with her dream job, a significant boost in pay, and no added debt.

2) PRESENT -- She lives simply. Present expenses can easily drain all our money if we let them. By living simply, being contented with small luxuries and finding value in non-material wealth (relationships, nature, and so on), she keeps her day-to-day expenses moderate.

3) FUTURE -- She made investments in both land and capital. When buying a home, she deliberately sought out properties that would allow her to generate rental income. Whenever she received a financial gift or bonus, she put it toward mortgage debt or capital investments like index funds and bonds.

She is not what most would consider wealthy, but she has built up for herself secure streams of income that are likely to last for the rest of her life. She is financially free, master of her own time, and she has never been more alive or happy.

Your Turn

To make this concept practical, you need to take stock. Where are your income streams springing from now? If you stopped laboring today, how much income would your current land and capital investments produce for you every month? What are some ways you might be able to make more out of the resources you currently have?

Where is your current income flowing to? What percentage is paying off money borrowed in the past? What percentage is being put toward your future? When you look at those numbers, do you think they are in balance?

Who do you know that has achieved financial independence, and how did they use land or capital to do so? How might you direct your own funds toward land and capital in a way that will create steady income down the road?

.png)