In part 1 of this article, we looked at three arguments against index funds. Here we will discuss some other arguments.

4 | Passive funds own all the bad stocks.

This premise is true, but the implication that it makes passive investing a bad strategy is not. Think about the payoff structure for stocks. The most they can ever lose is 100%, but their upside is unlimited, so a few big winners can make up for the market’s many losers. Passive funds own them all. Those who attempt to avoid the bad stocks risk missing out on the big winners, which have historically accounted for the lion’s share of the market’s long-run returns.

5 | Passive funds don’t offer any downside protection.

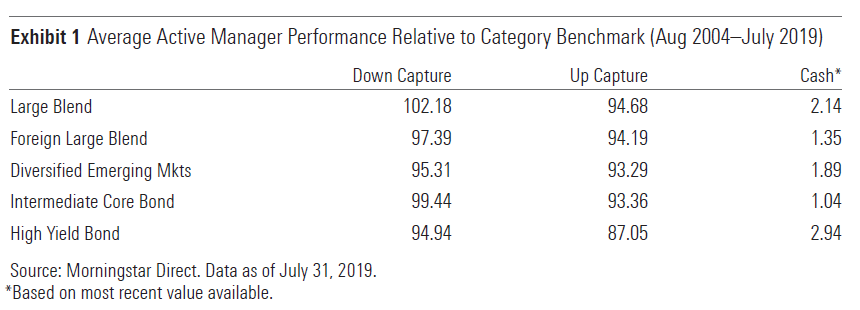

This is also true, but it doesn’t diminish the case for index investing. Most active managers haven’t offered much better downside protection than their respective Morningstar Category indexes over the trailing 15 years through July 2019, as Exhibit 1 shows. While some active managers offer slightly better downside protection than their benchmarks, it’s often partially because of the cash balances they keep on hand to meet redemptions. But rather than paying an active manager to hold cash, investors can do that themselves and just invest a little less in an index fund. A minimum-volatility fund could also provide some downside protection.

6 | Forced index trades may create high transaction costs that can hurt performance.

This is a valid concern. When securities are added to or removed from an index, it forces managers who track the index to buy or sell those securities, regardless of price. Those concentrated trades can push prices away from the managers, hurting the performance of the index. In fact, much of the price impact happens before the index changes go into effect, as index arbitragers buy securities scheduled to be added to the index, in anticipation of index demand, and sell securities slated for removal.

These hidden costs tend to be bigger for less-liquid securities, like small-cap stocks, than for large-cap stocks, but they still matter there, too.2 It seems they should also increase with the amount of money tied to an index, but it appears these costs peaked around two decades ago and have declined since, while index investing has continued to grow.2,3 Perhaps the market is getting better at anticipating these changes before they’re announced, but it’s hard to say.

However, investors can largely avoid these costs by sticking to total market index funds. Total market indexes include everything, so if a stock’s price gets bid up in anticipation of it joining a narrower index, like the S&P 500, they benefit. Similarly, if forced selling pressure temporarily depresses a stock’s price after it’s removed from an index, a total market index will continue to hold it and capture the rebound.

7 | The growth of index investing can reduce the strength of corporate oversight and lead to less competition.

This argument isn’t very persuasive. The idea is that if asset managers own all companies in an industry, they want them all to do well and won’t push individual companies to aggressively compete to take market share away from others. However, there are a few reasons to believe that index ownership wouldn’t necessarily lead to less competition.

First, corporate managers are given incentives to promote their own firms’ best interest. Their compensation is usually closely tied to their company’s stock performance and meeting growth and profitability targets.

Second, it’s often not in a firm’s individual best interest to increase its competitive behavior. For example, if General Motors GM were to cut the price on its Chevrolet Silverado pickup to gain market share from Ford F, it knows that Ford is likely to follow suit, and both will be worse off.

Index managers don’t simply focus on competitive strategy or pricing in their engagements with their portfolio companies. Rather, they focus on corporate governance, making sure managers’ interests are aligned with investors’ and that each firm is appropriately managing risks. Even if index managers wanted to influence corporate strategy, it isn’t necessarily in their interest to maximize the profits of a specific industry because they own firms in all industries, and higher profits in one may equate to lower profits in another.

Passive Investing Isn’t So Bad

While passive investing isn’t perfect, it is not a bad idea to let the market work for you. The competition for market-beating performance is a zero-sum game, where the benefits largely accrue to the firms charging the fees. If you don’t work on Wall Street, the rise of passive investing isn’t something to fear.

2 Petajisto, A. 2010. “The index premium and its hidden cost for index funds.” https:// pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7205/cff1a6d50f57e2f9158f542945ce80255faf.pdf

3 S cari, C. 2016 “On the Changes to the Index Inclusion Effect with Increasing Passive Investment Management.” https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=joseph_wharton_scholars

.png)